“Creator’s blessing rests on the ones who make peace;

it will be said of them, ‘They are the children of the Great Spirit!’”

—Matthew 5:9, First Nations Version (InterVarsity Press)

I’d like to share with you something I’m adapting here from my reflections, as a woman with indigenous ancestry, at our staff’s annual fall retreat this week. As a typically happy joyful person, I at first intended something upbeat. It was a glorious fall day in a beautiful retreat setting, and we enjoyed it to the fullest! But for a week during which we celebrate Indigenous People’s Day, for a portion of our time I decided to invite our team to sit with complexity of the story of this land—our home—and the places we now steward on behalf of our city’s vulnerable people.

In conversation afterward, we were struck again by the fact that Joshua Station, one of our communities for redemptive transformational housing, sits on a historical site of great significance in Colorado’s story. In the fall of 1864 directly across our street, troops made their preparations to ride east.

Acknowledgment

This morning we pause in gratitude for the land on which we gather. This is land that has long been a place of life, gathering, and ceremony not just for Mile High Ministries and friends, but also for the Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Ute peoples. Before it received many of its current names, this region thrived as part of a vast network of homelands, trade routes, and sacred spaces extending across the Front Range and Great Plains.

The Arapaho called this place Heniini’i, meaning “people,” and traveled along the South Platte River that still winds nearby. The Cheyenne camped and traded through these same plains, shaping strong communities of kinship and resilience. And the Ute, among Colorado’s oldest continuous inhabitants, followed the rhythms of the mountains and valleys, guided by the seasons and stories of their ancestors.

Today, we acknowledge that colonization and forced displacement attempted to sever those relationships…through broken treaties, the violence of Sand Creek, and the taking of lands that were never freely given. Yet we also acknowledge that Indigenous presence did not end with those injustices. It endures. The Northern Arapaho Tribe, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, the Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma, the Southern Ute Indian Tribe, and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe all remain active keepers of culture, wisdom, and community in this region and beyond.

We honor their past, present, and future leadership, and we recognize that honoring land means standing with those who continue to protect and restore it.

May this acknowledgment not stop here during our time together, but be an opening invitation to learn from Indigenous teachers, to amplify Native voices, to support Native-led movements, and to cultivate right relationship with both the land and the peoples to whom it has always belonged.

May we move forward with humility, gratitude, and solidarity. May we seek not just to remember history, but to help write a more just and connected future.

Story

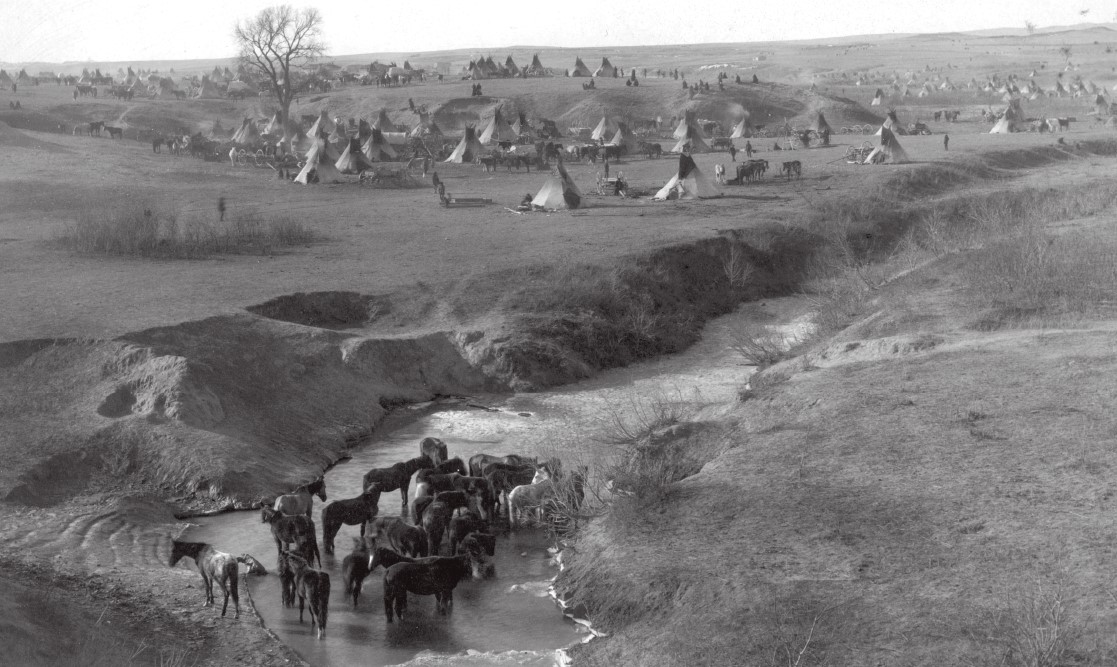

In the 1850s, as white settlers poured into the Colorado Territory during the Gold Rush, treaties between the U.S. government and Plains tribes were systematically broken.

The Treaty of Fort Laramie (1851) and later the Treaty of Fort Wise (1861) had reduced Cheyenne and Arapaho lands from over 40 million acres to just a small area along the Arkansas River in land that was mostly arid and unsuitable for sustaining life.

Many tensions grew between settlers and Native peoples as Indigenous nations, now confined and starving, continued to move across ancestral lands. Skirmishes between some Native groups and settlers led the U.S. military and local militias to adopt an increasingly violent stance toward all Native presence in the region.

Colonel John M. Chivington, a Methodist preacher turned militia officer, led a force of about 675 volunteer soldiers (mostly from the 1st and 3rd Colorado Cavalry) in a pre-dawn attack on a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho along Sand Creek.

This camp was under the leadership of Chief Black Kettle, who had been explicitly told by U.S. officials to camp there for protection under an American flag and a white flag of peace. Many of the people in the village believed they were under U.S. government protection.

Instead, Chivington ordered his troops to “kill and scalp all, big and little.”

What followed was a brutal massacre:

- Between 150 and 230 Indigenous people were killed, the majority of them women, children, and the elderly. (Most able bodied men were absent at the time, hunting food.)

- Bodies were mutilated; soldiers took scalps and intimate body parts as trophies and paraded them in Denver.

- Survivors fled into the freezing plains, and word of the atrocity spread rapidly through Indigenous and settler communities alike.

While celebrated by a downtown parade and triumphant reporting in the Rocky Mountain News, details of the massacre shocked even a few white officials and soldiers.

- S. congressional investigations (1865) confirmed that the attack had been unprovoked and brutal.

- Despite this, Chivington faced no punishment, resigning from the military before he could be court martialed.

- The massacre deepened mistrust and ignited decades of warfare between the U.S. and Plains tribes.

- False narratives about a “military victory” persisted well into the next century.

- For the Cheyenne and Arapaho, it became a foundational wound and collective trauma that continues to shape their memory, ceremony, and identity.

Today

The Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site (established in 2007 and managed by the National Park Service in collaboration with the Northern Cheyenne, Northern Arapaho, and Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma) preserves the site as a place of remembrance, grief, and healing.

Every October/November, descendants and allies gather for the Sand Creek Spiritual Healing Run/Walk, a multi-day journey from the massacre site to Denver. It ends with ceremonies at the Colorado State Capitol, honoring those lost and calling for ongoing truth-telling, justice, and repair.

For Denver-area organizations, this event is a direct link to the very ground we live and work on. It’s not just distant history.

The militia that attacked Sand Creek departed from Denver. (A plaque now marks the site 810 Vallejo Street.) The massacre itself was justified in the name of “protecting” settlers here. Recognizing that means acknowledging that our city’s foundations are interwoven with both violence and resilience. It also means that we now inherit the responsibility to participate in repair!

Response

A faithful response might include:

- Learning and teaching the story of Sand Creek accurately.

- Supporting descendant tribes’ memorial and education initiatives.

- Attending or supporting the Sand Creek Healing Run (prayer, sponsoring a meal, etc.)

- Making sure our acknowledgments don’t just lament the past, but commit to relationship, justice, and return.

The wind still carries the prayers of those who lived and died there.

Wisdom and Light

When Jesus says, “Blessed are those who mourn,” he dignifies the tears of the earth itself. This is the kind of mourning that doesn’t do the easy thing by turning away from pain, but rather names it so healing can begin.

When he says, “Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth,” he blesses those who never sought to dominate it, but to live in reciprocity with it, as the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Ute peoples have done for generations.

The Beatitudes (“Blessings of the Good Road,” in the First Nations Version) invite us to see blessing in humility, hunger for justice, and mercy, not in comfort or conquest. And to remember Sand Creek is to step into that blessing and to hunger and thirst for righteousness in our own time.

Formation here, in this city built upon that history, means being willing to hold grief and grace in the same breath. It also means hearing Jesus’ voice not as abstract comfort, but as a radical and present call: “You are the light of the world. A city built on a hill cannot be hidden.” (Matthew 5:14)

What would it mean for Denver, the very city from which the soldiers rode, to shine a different kind of light now?

- A light that tells the truth.

- A light that repents and repairs.

- A light that learns from those who have survived and who still lead the way toward life.

We gather today on land that holds stories older than any of us. These are stories of people, struggle, faith, and survival. Sharing the history of the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Ute peoples and the tragic events of Sand Creek isn’t meant to be an exercise in guilt. It’s an act of truth-telling, healing, and belonging.

As staff at Mile High Ministries, our work is grounded in the pursuit of home. We’re in the business of helping others rebuild it, rediscover it, or believe it’s possible again. But before we can help others find home, we must understand the land we stand on and the stories it carries.

In an age where history is being whitewashed, remembering becomes resistance.

It is a way of refusing amnesia. It’s a way of honoring those whose stories were silenced or erased. And it’s a way of ensuring we do not repeat the mistakes of our collective past.

We tell these stories because good things and even sacred things can grow from land marked by pain, but only if we’re willing to name the truth of what came before.

Acknowledgment doesn’t diminish what we’re doing today in this staff retreat, and the fun we’re going to have; it deepens it. It grounds our good work in humility.

Soil Tending

When we remember that the beauty of this place exists alongside the cost of displacement and loss, we learn to hold complexity and to be both grateful and honest, hopeful and repentant. That’s the soil of real formation.

Ultimately, this teaching reminds us that we all come from somewhere! Every one of us carries a story of migration, exile, longing, or belonging. So, to honor Indigenous peoples is also to honor the sacredness of origin itself and the truth that all of us are guests here, and that home is something we build and rebuild together in mutual care.

In telling the truth about this land, we become part of a larger story…one that bends toward justice, healing, and homecoming for all.

Reflection Questions

- Which Beatitude feels most alive in you as you hear the story of Sand Creek?

- What might it mean for our community to be salt and light in the place where violence once began?

- How can we embody peacemaking as formation — not sentimentally, but structurally?

— Miriam Medina, Director of Formation

The Great Sioux Indian Camp on River Brule Near Pine Ridge, South Dakota, 1890/1891, photographer: Grabill, J.C.H.